G.R. No. 249027, April 3, 2024,

♦ Decision,

Singh, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

Gesmundo, [CJ]

♦ Dissenting Opinion,

Leonen, [J]

♦ Concurring Opinion,

Caguioa, [J]

EN BANC

[ G.R. No. 249027, April 03, 2024 ]

NARCISO B. GUINTO (RELEASED AND REARRESTED PRISONER N216P-3611), INMATES OF NEW BILIBID PRISON INCLUDING ROMMEL BALTAR, ESMUNDO MALLILLIN, ALDRIN GALICIA, HENRY ALICNAS, DENMARK JUDERIAL, JUANITO MIÑON, JR., FROMENCIO ENACMAL, BENJAMIN IBAÑEZ, RICKY BAUTISTA, LEDDIE KARIM, ALFREDO ROMANO, JR., MARIO SARMIENTO, DANILO MORALES, AND ALEX RIVERA, PETITIONERS, VS. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, BUREAU OF CORRECTIONS, BUREAU OF JAIL MANAGEMENT AND PENOLOGY, AND PHILIPPINE NATIONAL POLICE, RESPONDENTS.

[G.R. No. 249155]

INMATES OF NEW BILIBID PRISON, AS REPRESENTED BY RUSSEL A. FUENSALIDA, TOSHING YIU, BENJAMIN D. GALVEZ, CERILO C. OBNIMAGA, URBANO D. MISON, ROLAND A. GAMBA, PABLO Z. PANAGA, AND ROMMEL T. DEANG, PETITIONERS, VS. SECRETARY MENARDO GUEVARRA, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, SECRETARY EDUARDO AÑO, DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, DIRECTOR GENERAL GERALD BANTAG, BUREAU OF CORRECTIONS, AND HON. ALLAN SULLANO IRAL, CHIEF, BUREAU OF JAIL MANAGEMENT AND PENOLOGY, RESPONDENTS.

CONCURRING OPINION

CAGUIOA, J.:

I am in full agreement with the ponencia. The 2019 Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations (2019 Revised IRR) of Republic Act No. 10592,1 insofar as it excluded recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees, and persons convicted of heinous crimes from enjoying the benefit of a good conduct time allowance (GCTA) after their final conviction, should be nullified.

For convicted prisoners to avail themselves of GCTA credits earned during the service of their sentence after final conviction, Republic Act No. 10592 only requires that they have to be "in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail."2 Thus, there was no basis for the exclusion by the 2019 Revised IRR of recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees, and persons convicted of heinous crimes from earning GCTA after their final conviction if they are in a penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center, or in a local jail.

Factual background

As narrated in the ponencia, Republic Act No. 10592 amended Articles 29, 94, 97, and 98 of the Revised Penal Code. Section 1 of Republic Act No. 10592 amended Article 29 of the Revised Penal Code (on deducting the period of preventive imprisonment from the term of imprisonment) by including the proviso "recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crimes are excluded from the coverage of this Act."

Meanwhile, Section 3 of Republic Act No. 10592 amended Article 97 of the Revised Penal Code (allowance for good conduct, i.e., GCTA), by allowing qualified offenders under Article 29 to earn GCTA credits even during preventive imprisonment. Par. 1 of Article 97 now reads as follows: "The good conduct of any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code, or of any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail shall entitle him [or her] to the following deductions from the period of his [or her] sentence."3

Republic Act No. 10592 empowered the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) to issue the implementing rules and regulations that resulted in the issuance of the 2019 Revised IRR. Section 2, Rule IV of the 2019 Revised IRR reads:

SECTION 2. GCTA during Service of Sentence. — The good conduct of a [Person Deprived of Liberty (PDL)] convicted by final judgment in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail shall entitle him [or her] to the deductions described in Section 3 hereunder, as GCTA, from the period of his [or her] sentence, pursuant to Section 3 of [Republic Act] No. 10592.ℒαwρhi৷

The following shall not be entitled to any GCTA during service of sentence:

a. Recidivists;

b. Habitual Delinquents;

c. Escapees; and

d. PDL convicted of Heinous Crimes. (Emphasis supplied)

Under Section 2 of the 2019 Revised IRR, the DOJ and the DILG extended the exclusionary proviso "recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crimes are excluded from the coverage of this Act"4—which, to reiterate, applies only to the entitlement of deducting one's preventive imprisonment from the full term of the imprisonment under Section 29—to Article 97 of the Revised Penal Code. Effectively, the 2019 Revised IRR excluded recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and those convicted of heinous crimes from earning GCTA altogether, whether during their preventive imprisonment or after final conviction.

Petitioners are inmates convicted of heinous crimes. When the Court, in Inmates of New Bilibid Prison v. De Lima,5 ordered the recomputation of time allowances for the petitioners therein and "those who are similarly situated,"6 the respondents DOJ, Bureau of Corrections, Bureau of Jail Management and Penology excluded petitioners from those who would be granted GCTA earned during the service of their sentence pursuant to the 2019 Revised IRR.

Petitioners then filed Petitions for Certiorari and Prohibition (Petitions) praying: (a) for the issuance a status quo ante order; (b) for a declaration that any convict, including those convicted of heinous crimes, are not prohibited from earning GCTA after conviction; and (c) for the Court to enjoin the respondents to recompute the time allowance for those convicted of heinous crimes.

The ponencia grants the Petitions for the following reasons. First, Section 3 of Republic Act No. 10592 established two categories of persons entitled to earn GCTA, "which are: (1) any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment, pursuant to Article 29 of the [Revised Penal Code], as amended by Section 1 of [Republic Act No.] 10592, and (2) any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation, or detention center in any other local jail."7 The only qualification for the second category is that the convicted prisoner be in "any penal institution." Second, the DOJ exceeded its rule-making powers granted by Republic Act No. 10592 when it "[expanded] the scope of offenders who cannot earn GCTA credits, to the latter's prejudice."8

Legislative history concerning GCTA

Before the Revised Penal Code and Republic Act No. 10592, Act No. 15339 allowed "prisoners convicted of any offense"10 and "sentenced for a definite term of more than 30 days and less than life" to reduce their sentence through their good conduct in the service thereof. Section 1 of Act No. 1533 provides:

SECTION 1. Each convict who is sentenced for a definite term of more than thirty days and less than life shall be entitled to diminish the period of his [or her] sentence under the following rules and regulations:

(a) For each full month, commencing with the first day of his [or her] arrival at a provincial or Insular jail or prison, during which he [or she] has not been guilty of a violation of discipline or any of the rules of the prison, and has labored with diligence and fidelity upon all such tasks as have been assigned to him [or her], he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of five days from the period of his [or her] sentence.

(b) After he [or she] has served two full years of a sentence, the deduction shall be eight days for each month thereafter.

(c) After he [or she] has served five full years of a sentence, the deduction shall be ten days for each month thereafter.

(d) After he [or she] has served ten full years of his [or her] sentence, the deduction from his [or her] term shall be fifteen days for each month thereafter.

Notably, Section 5 of Act No. 1533 extended the right to earn GCTA to detention prisoners before conviction, to wit:

SECTION 5. Detention prisoners who voluntarily offer in writing to perform such labor as may be assigned to them shall be entitled to a credit in accordance with the provisions of this Act, which shall be deducted from such sentence as may be imposed upon them in the event of their conviction. (Emphasis supplied)

The intention of Congress in allowing prisoners to earn GCTA was twofold: first, GCTA encouraged the convict to reform and to acquire habits of industry that will not be forgotten after he or she has served his or her sentence; and second, GCTA was a disciplinary aid within the various jails and penitentiaries. The Court in Frank v. Wolfe11 explained:

The provisions of the Act [No. 1533] are in accord with approved principles of penology, adopted by most modern states, and it is evident from the terms of the Act itself that it was the intention of the lawmaker that all convicts serving sentences for more than thirty days and less than life should be entitled to the benefits conferred thereby. We would be loath, therefore, to construe doubtful language in a grant of commutation so as to defeat the object of the statute and thwart the wise purpose of the lawmaker; and unless the language of a grant of a pardon or commutation were so clear and explicit as to leave no room for doubt, we would not feel justified in costruing it so as to impute to the Chief Executive the purpose so to do, unless some sound reason were suggested as a basis for his [or her] action in a particular case.

The Act has a double purpose: it is intended to encourage the convict in an effort to reform, and to induce him for her) to acquire habits of industry and good conduct which will not be forgotten after he [or she] has served his (or her) sentence; and it is intended as an aid to discipline within the various jails and penitentiaries; thus the dictates of humanity and the interests of the public service would seem to negative a doubtful construction of a grant of a commutation which would tend to impair the usefulness of the Act as a means to the end which it was sought to secure by its enactment, unless, as we have stated before, some sound reason can be suggested for an exception in a particular case.12 (Emphasis Supplied)

In Frank v. Wolfe, the Court noted that the legislative intent in enacting Act No. 1533 was to entitle all convicts to GCTA. Thereafter, the right to earn GCTA was carried over to the Revised Penal Code under Article 94, which prescribed the ways that criminal liability may be partially extinguished:

ARTICLE 94. Partial extinction of criminal liability.—Criminal liability is extinguished partially:

1. By conditional pardon;

2. By commutation of the sentence; and

3. For good conduct allowances which the culprit may earn while he [or she] is serving his [or her] sentence. (Emphasis supplied)

However, Section 5 of Act No. 1533, which extended to detention prisoners the right to earn GCTA before their conviction, was not carried over to the Revised Penal Code. Thus, before Republic Act No. 10592, a deduction based on good conduct (i.e., the GCTA) was only available to those convicted and serving their sentence in a penal institution under Article 97 of the Revised Penal Cede.

In this connection, the Court in People v. Martin13 declared that GCTA was only available after conviction while the convict was serving his or her sentence, to quote: "[t]his allowance is given in consideration of the good conduct of the prisoner while serving his [or her] sentence. Not having served this remitted penalty, there is no reason for the allowance, namely, the good conduct of the appellant while serving his sentence."14

During the deliberations, a sound and insightful point was raised that when Act No. 1533 was enacted the crimes that are today considered heinous crimes were the same crimes punished in 1906 with reclusion perpetua under the 1870 Spanish Penal Code (at that time an indefinite penalty comparable to "life imprisonment" as we know today). Hence, persons in 1906 who were convicted of crimes that we now call "heinous crimes" were sentenced to serve the penalty of "life" imprisonment and were thus excluded from earning GCTA.

Consequently, it was asserted that when (a) when Act No. 1533 excluded persons serving life sentences from earning GCTA and (b) in 1906 the crimes that carried life sentences are the same crimes that are considered heinous crimes today, (c) Act No. 1533 is evidence of the principle that persons convicted of heinous crimes are excluded from earning GCTA.

On the contrary, the argument incorrectly considers the terms "heinous crimes" and "crimes carrying life sentences" as equivalents simply because the two coincided in 1906. To my mind, these are two different terms that do not always coincide, which is evidently the case today. In 1906, the reason why persons convicted of heinous crimes and serving life sentences could not avail themselves of GCTA was not because of the crime they committed, but because the penalty, i.e., imprisonment for life or less than 30 days, rendered GCTA meaningless for these persons.

Precisely, those persons who were excluded by Act No. 1533 from earning GCTA were those convicts who could derive no tangible benefit from GCTA. This exclusion was not because of the crime they committed or as some kind of additional punishment for the gravity of their offense but because of the nature of the penalties. Thus:

Persons who had prison sentences of less than 30 days would be released even before their GCTA could be credited since the minimum period to earn GCTA is a "full month;" and

Persons serving life sentences would naturally derive no benefit from GCTA since their sentence is precisely to remain in prison for the rest of their lives. It would thus be a futile exercise to grant one a "deduction" to a life sentence.

The same logic applies with even more force with respect to the persons sentenced to the death penalty for obvious reasons.

The underlying principle that can be gleaned from the foregoing is that any convict who has an expectation to be released from prison and returned to society in the future, is entitled to earn GCTA. Thus, when Act No. 1533 in its title uses the phrase "all convicts," Congress necessarily meant all those convicts for whom GCTA could have some tangible benefit.

Moreover, heinous crimes are presently punished by reclusion perpetua, which has a maximum period of imprisonment of 40 years.15 As the Court declared in People v. Retuta,16 "the penalty of 'life imprisonment' does not appear to have any definite extent or duration."17 Thus, the persons convicted of heinous crimes are no longer serving indefinite life sentences as they were in 1906. Accordingly, the principles embodied in Act No. 1533 suggest that the Revised Penal Code still allowed these persons to earn GCTA.

The Death Penalty Law

The legislative history of Republic Act No. 765918 or the "Death Penalty Law" is also instructive to provide context on why persons convicted of heinous crimes are entitled to earn GCTA credits after conviction and during the service of their sentence. In 1993, during the enactment of Republic Act No. 7659, an attempt was made to further restrict the right of convicted prisoners to earn GCTA by disqualifying those convicted of heinous crimes from earning the same. This attempt, however, was rejected by Congress as will be discussed below.

Republic Act No. 7659 was a consolidation of Senate Bill No. 891 and House Bill No. 62. Notably, Senate Bill No. 891 sought to amend Article 27 of the Revised Penal Code:

by inserting therein what are to be considered heinous crimes and to penalize these not with the death penalty, but with reclusion perpetua only, with the qualification that "any person sentenced to reclusion perpetua for ... [such heinous] crimes under this Code shall be required to serve thirty (30) years, without entitlement to good conduct time allowance and shall be considered for executive clemency only after service of said thirty (30) years."19 (Emphasis supplied)

This amendment, however, was not adopted in the final text of Republic Act No. 7659.20

Amendments under Republic Act No. 10592

With the enactment of Republic Act No. 10592, Congress struck the middle ground between (a) Section 5 of Act No. 1533 in allowing, without qualification, detention prisoners to earn GCTA before conviction, "which shall be deducted from such sentence as may be imposed upon them in the event of their conviction," and (b) the proposed amendment in Senate Bill No. 891, in relation to Republic Act Ne. 7659 disqualifying persons convicted of heinous crimes from earning GCTA altogether. In other words, under Republic Act No. 10592, Congress entitled detention prisoners to earn GCTA during the time of their preventive imprisonment before conviction but excluded therefrom persons charged with heinous crimes.

To illustrate, Article 97 of the Revised Penal Code, before and after the amendments of Republic Act No. 10592, is shown below for comparison:

| Article 97 (before Republic Act No. 10592) |

Article 97, as amended by Republic Act No. 10592 |

|

ARTICLE 97. Allowance for good conduct.—The good conduct of any prisoner in any penal institution shall entitle him [or her] to the following deductions from the period of his [or her] sentence:

1. During the first two years of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of five days for each month of good behavior;

2. During the third to the fifth year, inclusive, of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of eight days for each month of good behavior;

3. During the following years until the tenth year, inclusive, of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of ten days for each month of good behavior, and

4. During the eleventh and successive years of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of fifteen days for each month of good behavior.

|

ARTICLE. 97. Allowance for good conduct.—The good conduct of any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code, or of any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail shall entitle him [or her] to the following deductions from the period of his [or her] sentence:

1. During the first two years of imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of twenty days for each month of good behavior during detention;

2. During the third to the fifth year, inclusive, of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a reduction of twenty-three days for each month of good behavior during detention;

3. During the following years until the tenth year, inclusive, of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of twenty-five days for each month of good behavior during detention;

4. During the eleventh and successive years of his [or her] imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed a deduction of thirty days for each month of good behavior during detention; and

5. At any time during the period of imprisonment, he [or she] shall be allowed another deduction of fifteen days, in addition to numbers one to four hereof, for each month of study, teaching or mentoring service time rendered.

An appeal by the accused shall not deprive him [or her] of entitlement to the above allowances for good conduct. (Emphasis supplied)

|

Republic Act No. 10592 thus extended the right to earn GCTA to "any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code." It is evident from Article 29, as amended, that GCTA may be earned even during the period of preventive imprisonment by any offender or accused, as long as he or she is not a recidivist, habitual delinquent, escapee, or person charged with heinous crimes, viz.:

ARTICLE. 29. Period of preventive imprisonment deducted from term of imprisonment. — Offenders or accused who have undergone preventive imprisonment shall be credited in the service of their sentence consisting of deprivation of liberty, with the full time during which they have undergone preventive imprisonment if the detention prisoner agrees voluntarily in writing after being informed of the effects thereof and with the assistance of counsel to abide by the same disciplinary rules imposed upon convicted prisoners, except in the following cases:

1. When they are recidivists, or have been convicted previously twice or more times of any crime; and

2. When upon being summoned for the execution of their sentence they have failed to surrender voluntarily.

If the detention prisoner does not agree to abide by the same disciplinary rules imposed upon convicted prisoners; he [or she] shall do so in writing with the assistance of a counsel and shall be credited in the service of his [or her] sentence with four-fifths of the time during which he [or she] has undergone preventive imprisonment.

Credit for preventive imprisonment for the penalty of reclusion perpetua shall be deducted from thirty (30) years.

Whenever an accused has undergone preventive imprisonment for a period equal to the possible maximum imprisonment of the offense charged to which he [or she] may be sentenced and his [or her] case is not yet terminated, he [or she] shall be released immediately without prejudice to the continuation of the trial thereof or the proceeding on appeal, if the same is under review. Computation of preventive imprisonment for purposes of immediate release under this paragraph shall be the actual period of detention with good conduct time allowance: Provided, however, That if the accused is absent without justifiable cause at any stage of the trial, the court may motu proprio order the rearrest of the accused: Provided, finally, That recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crimes are excluded from the coverage of this Act. In case the maximum penalty to which the accused may be sentenced is destierro, he [or she] shall be released after thirty (30) days of preventive imprisonment. (Emphasis supplied)

When Article 29 provides that the "computation of preventive imprisonment for purposes of immediate release ... shall be the actual period of detention with good conduct time allowance," it recognized that GCTA can be earned during preventive imprisonment—i.e., that good conduct during the period of preventive imprisonment can give rise to good conduct time allowance in addition to the deduction of the entire period of preventive imprisonment. To be sure, the bills that eventually became Republic Act No. 10592 explained that "it is unfortunate that under present laws, prisoners are not entitled to good conduct allowance while their cases are on appeal. This rule either discourages prisoners from complying with prison rules or withdrawing their appeals to qualify for good conduct allowance."21 Thus, Republic Act No. 10592, which allows qualified offenders or accused under Article 29 to earn GCTA credits even during the period of their preventive imprisonment, was set in stone.

Article 29 vs. Article 97

At this point, it is important to distinguish the deductions granted under Articles 29 and 97 of the Revised Penal Code.

Article 29 primarily pertains to the deduction of the time of one's preventive imprisonment from one's total sentence once the person is convicted by final judgment and begins to serve his or her adjudged sentence. This is separate and distinct from the deduction granted according to one's GCTA under Article 97. That said, the deduction that Article 29 speaks of is not the subject of this case, as the present Petitions only involve the question of a convict's eligibility to avail himself or herself of GCTA under Article 97. Stated differently, the petitioners—who were adjudged guilty of heinous crimes—are not asking the respondents to deduct the time they were preventively imprisoned from the total term of their imprisonment. Neither are they asking for the right to earn GCTA during the time they were preventively imprisoned. Rather, they are asking the respondents to make a deduction of the requisite period provided by Article 97 based on their alleged good conduct after their conviction by final judgment.

I wholly agree with the ponencia that Article 97 of the Revised Penal Code, as amended, speaks of two categories of persons entitled to GCTA. For reference, the text of Article 97, as amended, is as follows:

ARTICLE 97. Allowance for good conduct.—The good conduct of any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code [(the first phrase)], or of any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail shall entitle him [or her] to the following deductions from the period of his [or her] sentence [(the second phrase)]. (Emphasis supplied)

The presence of the comma and the conjunction "or" separating the first and second phrases is necessarily persuasive that the first and second phrases are distinct categories within the meaning of Article 97. Accordingly, the two categories of persons entitled to GCTA are:

(a) "any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code;" and

(b) "any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail."

The phrase "qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code" only modifies the noun "offender" found in the first phrase. In contrast, the noun in the second phrase is "prisoner" and it has two modifiers—the first is the adjective convicted and the second is the phrase "in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail." Thus, a prisoner may earn GCTA: (1) during the period of preventive imprisonment before conviction (when he or she is merely an "offender"), in addition to the period (2) while he or she is serving his or her sentence after conviction.22

For the first period, i.e., preventive imprisonment, Article 97 allows only those persons qualified to deduct their preventive imprisonment under Article 29 to earn GCTA during the period of their detention, which shall be deducted from their sentence in the event of their conviction.23

Whereas for the second period, i.e., after conviction and service of his or her sentence, the Revised Penal Code and Republic Act No. 10592 provide no other qualifications for the grant of GCTA apart from the prisoner being "in any penal institution, rehabilitation, or detention center or any other local jail."24

Accordingly, Articles 29 and 97, as amended by Republic Act No. 10592, may be distinguished as follows:

| Criterion |

Article 29 |

Article 97 |

| Period to be deducted from the sentence or term of imprisonment upon conviction |

Total period of detention during preventive imprisonment |

Graduated scale of 20 to 30 days per month of good conduct earned: (1) during preventive imprisonment; and (2) during service of sentence after conviction by final judgment. |

| Who are qualified to avail of the deductions |

Any offender or accused except:

1. "Recidivists"

2. Those who "have been convicted previously twice or more times of any crime" (habitual delinquents)

3. Those who "upon being summoned for the execution of their sentence they have failed to surrender voluntarily" (escapees)

4. Persons charged with heinous crimes

|

1. For GCTA during detention while under preventive imprisonment:

1. "Recidivists"

2. Those who "have been convicted previously twice or more times of any crime" (habitual delinquents)

3. Those who "upon being summoned for the execution of their sentence they have failed to surrender voluntarily" (escapees)

4. Persons charged with heinous crimes

2. For GCTA during service of sentence (after conviction):

Any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail

|

| How to avail |

The detention prisoner agrees voluntarily in writing after being informed of the effects thereof and with the assistance of counsel to abide by the same disciplinary rules imposed upon convicted prisoners |

Performance of good conduct |

To illustrate, consider two prisoners—Pedro and Juan—who were charged and eventually convicted of qualified theft and parricide (a heinous crime), respectively. Pedro and Juan were sentenced to suffer the penalty of imprisonment for, hypothetically, 30 years. Pedro and Juan were charged, arrested, and detained on the same day, and both were preventively imprisoned for 10 years before they were convicted by final judgement at the end of their 10th year. Throughout their imprisonment, Pedro and Juan exhibited good conduct until the end of their 15th year.(awÞhi( Both Pedro and Juan are not recidivists, habitual delinquents, or escapees. When they were preventively imprisoned at the beginning of Year 1, they both agreed in writing to abide by the same disciplinary rules imposed on convicted prisoners. Their prison sentences, taking into consideration the effects of Republic Act No. 10592, are as follows:

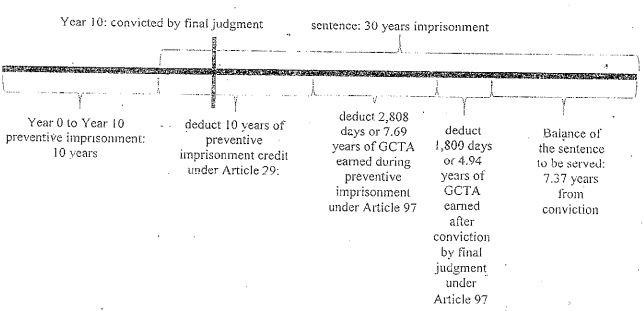

1. Pedro (not a recidivist, habitual delinquent, escapee or person charged with heinous crime) will be released from prison after serving 7.37 years, taking into account his period of preventive imprisonment, GCTA earned during preventive imprisonment, and GCTA earned after conviction by final judgment, computed as follows:

2. Juan (charged with a heinous crime and later convicted of one) will be released from prison after serving 25.06 years, taking into account only his GCTA earned after his conviction by final judgment, computed as follows:

.jpg)

Thus, guided by the foregoing discussion, recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons convicted of heinous crimes are not disqualified from earning GCTA credits after conviction by final judgment and during the service of their sentence. Otherwise stated, while they are excluded from deducting the period of their preventive imprisonment and prohibited from earning GCTA credits during the same period, nothing in Republic Act No. 10592 prohibits them from earning GCTA after their conviction by final judgment.

As earlier intimated, Section 2, Rule IV of the 2019 Revised IRR extended the proviso in Article 29 that disqualifies recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crimes to Article 97, both for GCTA earned during preventive imprisonment and after conviction.

Republic Act No. 10592 indeed deprives persons charged with heinous crimes of the benefit to earn GCTA during the period of their preventive imprisonment. They are not, however, disqualified from earning GCTA once convicted by final judgment and are serving their sentences. This is clear from the letter of Article 97, as amended by Republic Act No. 10592, that GCTA may be earned by "any convicted prisoner in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail." To be clear, the clause in Article 97 that "the good conduct of any offender qualified for credit for preventive imprisonment pursuant to Article 29 of this Code ... shall entitle him [or her] to the following deductions from the period of his [or her] sentence," refers to GCTA earned during the period of preventive imprisonment. The plain meaning of this clause is that only those qualified to deduct their preventive imprisonment from their sentence are allowed to earn GCTA credits during their preventive imprisonment. Otherwise stated, those disqualified under Article 29, i.e., recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees, and persons charged of heinous crimes, are also disqualified from earning GCTA credits, but only during their preventive imprisonment.

The 2019 Revised IRR effectively disregarded the distinctions between the two periods within which a prisoner may earn GCTA credits and thus denies them both to the petitioners even as the law deprives them of only one (i.e., GCTA earned during the period of their preventive imprisonment).

Consequently, the 2019 Revised IRR clearly went beyond the provisions of Republic Act No. 10592. Republic Act No. 10592 and the Revised Penal Code do not disqualify any convicted prisoner—regardless of the crime for which they were convicted—in a penal institution from earning GCTA.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I find it strange for Republic Act No. 10592 to recognize that recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crime are able to reform after conviction, but not during their preventive imprisonment.

Nevertheless, I respectfully submit that it is not the business of the Court to go against the express language of the law. Likewise, the doctrine of separation of powers proscribes the Judiciary from inquiring into the wisdom of the Congress in not totally preventing persons convicted of heinous crimes from earning GCTA credits during their preventive imprisonment. The case of Garcia v. Executive Secretary25 is instructive:

This legislative determination was a lawful exercise of Congress' prerogative and one that this Court must respect and uphold. Regardless of the individual opinions of the Members of this Court, we cannot, acting as a body, question the wisdom of a co-equal department's acts. The courts do not involve themselves with or delve into the policy or wisdom of a statute; it sits, not to review or revise legislative action, but to enforce the legislative will. For the Court to resolve a clearly non-justiciable matter would be to debase the principle of separation of powers that has been tightly woven by the Constitution into our republican system of government.26

To repeat, the subject of the present Petitions is the entitlement to GCTA credits earned during the service of final sentence, and to stress, the law does not disqualify anyone, including petitioners herein who were convicted of heinous crimes, from earning the same during the service of sentence, as long as they are "in any penal institution, rehabilitation or detention center or any other local jail."

All told, I CONCUR with the ponencia and vote that the Petitions should be GRANTED. Republic Act No. 10592 did not disqualify petitioners, and others similarly situated, from earning GCTA during the period of service of sentence after final conviction and deducting such credits from the term of their imprisonment. Section 2, Rule IV of the 2019 Revised IRR insofar as it excludes recidivists, habitual delinquents, escapees, and persons convicted of heinous crimes from earning GCTA under Article 97 of the Revised Penal Code, is null and void for going beyond the letter of the law.

Footnotes

1 Republic Act No. 10592 (2013), "An Act Amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98 and 99 of Act No. 3815, as amended, known as the Revised Penal Code."

2 Republic Act No. 10592 (2013), sec. 3, amending REV. PEN. CODE, art. 97.

3 Emphasis supplied.

4 REV. PEN. CODE, art. 29, as amended by Republic Act No. 10592, sec. 1.

5 854 Phil. 675 (2019) [Per J. Peralta, En Banc].

6 Id. at 713.

7 Ponencia, p. 16.

8 Id. at 20.

9 Act No. 1533 (1906), "An Act Providing For the Diminution Of Sentences Imposed Upon Prisoners Convicted Of Any Offense and Sentenced For A Definite Term Of More Than Thirty Days and Less Than Life In Consideration Of Good Conduct and Diligence."

10 Emphasis supplied.

11 11 Phil. 466 (1908) [Per J. Carson, En Banc].

12 Id. at 471.

13 68 Phil. 122 (1939) [Per C.J. Avanceña, Second Division].

14 Id. at 125.

15 REV. PEN. CODE, art. 27, as amended by Republic Act No. 7659.

16 304 Phil. 813 (1994) [Per J. Bellosillo, First Division].

17 Id. at 827.

18 Titled, "An Act to Impose The Death Penalty On Certain Heinous Crimes, Amending For That Purpose The Revised Penal Code, as amended, Other Special Penal Laws, and for Other Purposes."

19 People v. Lucas, 310 Phil. 77, 81 (1995) [Per J. Davide, En Banc].

20 See discussion in People v. Lucas, Id.

21 Explanotory Note of Senate Bill No 2462, An Act Amending Article 97 of Act No. 3815, Otherwise Known as the Revised Penal Code, filed by Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago on August 31, 2010.

22 See also REV. PEN. CODE, as amended by Republic Act No. 10592.

23 To use the language in Act No. 1533.

24 Emphasis supplied.

25 602 Phil. 64 (2009) [Per J. Brion, En Banc].

26 Id. at 77.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation