Manila

EN BANC

[ G.R. No. 226445, February 27, 2024 ]

TUNA PROCESSORS, INC., PETITIONER, VS. FRESCOMAR CORPORATION & HAWAII INTERNATIONAL SEAFOODS, INC.,* (HISI), RESPONDENTS.

[G.R. No. 226631]

HAWAII INTERNATIONAL SEAFOOD, INC., PETITIONER, VS. TUNA PROCESSORS, INC., RESPONDENT.

D E C I S I O N

LOPEZ, M., J.:

In this case, the Court stresses the importance of examining the patent claims in determining patent infringement. Like the technical description of a real property, patent claims define the extent of protection conferred by the patent and describe the boundary of the invention through words. Any information or invention outside of that boundary forms part of prior art, and the use of that information or invention without the patentee's consent does not constitute patent infringement.1

This resolves the consolidated Petitions for Review on Certiorari,2 assailing the Court of Appeals' (CA) Decision3 dated September 9, 2015 and Resolution4 dated August 10, 2016 in CA-G.R. CV No. 02845-MIN.

The core issues are whether (1) Frescomar Corporation's (Frescomar) smoke production infringed Philippine Patent No. 31138, entitled "Method for Curing Fish and Meat by Extra Low Temperature Smoking," or the Yamaoka Patent and (2) Hawaii International Seafoods, Inc. (HISI) is liable for tortious interference.5

The Facts

Kanemitsu Yamaoka owned the rights over the Yamaoka Patent,6 a process of curing tuna meat using filtered smoke cooled to between 0°C and 5°C. Yamaoka Nippon Corporation (YNC), and later Pescarich Manufacturing Corporation (Pescarich), used the Yamaoka Patent in producing tuna products.7

In January 2003, Tuna Processors, Inc. (TPI), a foreign corporation organized and existing under the laws of California, United States (U.S.) of America, was granted the right to license or sub-license the Yamaoka Patent and its counterparts in other jurisdictions, such as U.S. Patent No. 5,484,619 and Indonesian Patent No. ID0003911. TPI also had the exclusive right to enforce the patents and collect royalties for past and present infringement and damages from third persons.8

On March 31, 2004, TPI entered into a license agreement with Frescomar, a company that processes and manufactures seafood products and tasteless filtered smoke in canisters for export abroad.9 Under the License Agreement, TPI granted Frescomar the non-exclusive license to make, use, import, purchase, sell, or offer to sell products protected by the Yamaoka Patent. In turn, Frescomar has to submit shipment reports as the bases for computing the royalty fees for the use of the patent. If Frescomar believes that any of its products do not use the Yamaoka Patent, it should request for exemption from paying the royalty fees.10

Frescomar made an initial payment of USD 3,000.00 to TPI. However, Frescomar failed to make subsequent payments.11 In a letter dated October 30, 2004, TPI demanded from Frescomar the shipment report and payment of royalty fees.12 TPI's request remained unheeded.

In another letter dated September 1, 2005, TPI reiterated its previous demands. TPI added that it has come to their attention that Frescomar is producing and selling filtered smoke contained in a canister for William Kowalski (Kowalski) of HISI. TPI demanded that Frescomar submit all information for all transactions, which it believed to be outside the scope of the Yamaoka Patent, and stop using the patent to produce smoke for Kowalski.13

HISI likewise sells seafood products in the U.S. and Frescomar's tasteless smoke in a canister to seafood processing facilities outside the Philippines. HISI's products used the tasteless smoke technology protected under U.S. Patent No. 5,972,401 with a corresponding application under Philippine Patent Application No. 1-1998-02560, entitled "Process for Manufacturing Tasteless Super-Purified Smoke for Treating Seafood to be Frozen and Thawed" (Kowalski Patent).14

In response to TPI's demands, Frescomar initially claimed that the selling of smoke was not covered by the License Agreement.15 Not long after, Frescomar agreed to pay USD 22,534.80 royalties computed based on Frescomar's shipment reports submitted to TPI.16 Unfortunately, Frescomar failed to make any payments. TPI sent a final demand letter17 dated January 13, 2006 asking Frescomar to pay USD 22,534.80 royalties for the past two years. Still, Frescomar failed to comply. Consequently, TPI terminated the License Agreement on January 17, 2006.18

On February 13, 2006, Frescomar and HISI filed a Complaint for Unfair Competition and Injunction with Prayer for a Preliminary Injunction against TPI. In turn, TPI filed a Counterclaim demanding the payment of royalties from March 25, 2004 until the termination of the agreement.19 TPI's Counterclaim raised the issues of whether Frescomar and HISI are liable for breaching the License Agreement and infringing the Yamaoka Patent.20 Frescomar and HISI filed a Supplemental Reply (To Defendant's Answer with Compulsory Counterclaim and Opposition to the Application for Preliminary Injunction)21 and mainly argued that the Yamaoka Patent only covers tuna products and not tasteless smoke technology and that TPI has no right to stop Frescomar from producing the smoke and HISI from buying it.

On August 23, 2007, TPI and Frescomar entered into a Settlement Agreement.22 In a Joint Motion to Dismiss23 filed on September 25, 2007, Frescomar moved for the dismissal of its action against TPI, while TPI moved for the dismissal of its counterclaims against Frescomar, both with prejudice.24 On October 4, 2007, the Regional Trial Court, Branch 23, General Santos City (RTC) granted the Joint Motion to Dismiss. The dispositive portion states:

WHEREFORE, finding the Joint Motion to Dismiss to be in order, Civil Case No. 7565 is hereby ordered DISMISSED with prejudice. In Civil Case No. 7566, the same is hereby ordered DISMISSED with prejudice with respect to plaintiff [Frescomar] and said case shall continue with respect to plaintiff HISI.

SO ORDERED.25 (Emphasis supplied)

Thereafter, HISI moved to suspend the proceedings reasoning that it would file a Petition for Certiorari to question the RTC orders. The RTC granted the motion and suspended the proceedings.26

On April 11, 2008, the RTC eventually lifted the suspension since no Petition was filed. The case was referred to the Philippine Mediation Center. But before the scheduled mediation, TPI filed a Motion to Dismiss and to Set for Hearing the Counterclaim in the unfair competition case on the ground of failure to prosecute for an unreasonable length of time. Also, HISI filed a Motion to Dismiss the unfair competition case because Frescomar entered into a Settlement Agreement with TPI.27

Acting on TPI and HISI's motion, the RTC dismissed the unfair competition case on September 4, 2008 and directed TPI to present its evidence ex-parte for its counterclaims against HISI.28

TPI submitted the testimonies of (1) Frescomar's Vice President, Francisco Santos (Francisco), (2) YNC's former plant manager,29 Eliseo Garay (Eliseo), who worked with Yamaoka and was later hired by HISI as a Senior Technical Consultant, (3) Pescarich's former smoke machine operator, Shem Makiputin (Shem), (4) TPI's President, Jake T. Lu, (5) employee tasked to process litigation expense advances, to justify its litigation expenses, and (6) Andrestine Tan (Tan) and Charlie Ng (Ng) to support its claim for moral damages.30

TPI presented Francisco to prove that: (1) Frescomar entered into a License Agreement with TPI; (2) Kowalski was aware of the License Agreement; (3) Frescomar used the Yamaoka Patent from 2004 to 2007; (4) Frescomar delivered about 2,389 canisters of filtered smoke to HISI; (5) Frescomar did not pay the royalties after consulting Kowalski, who advised Frescomar to say that it was actually using his patent and not Yamaoka's; and (6) Frescomar filed the unfair competition case to pre-empt the arbitration proceedings in the US, which was required under the License Agreement.31

Next, Eliseo submitted that: (1) Frescomar had been using the smoke machine in the Yamaoka Patent to produce the smoke that it sells to HISI, which in turn sells them to other manufacturers; (2) the temperature used in Frescomar's process was within the temperature covered by the Yamaoka Patent; and (3) following Kowalski's instructions, he ordered the falsification of the daily record of temperature to make it appear that the temperatures they used fall within the Kowalski Patent and outside the Yamaoka Patent.32

Shem supported Eliseo's testimony that they antedated the 2004 to 2006 records to make it appear that the temperature range fell outside the Yamaoka Patent. Also, he confirmed that Frescomar hired him to operate two machines patterned after Pescarich's smoke machines.33

Jake T. Lu demonstrated TPI's right over the Yamaoka Patent and the License Agreement with Frescomar, including Frescomar's failure to comply with the terms of the agreement. He further testified that TPI filed a patent infringement case against HISI in the U.S. sometime in December 2004,34 and Frescomar believed that if it pays the royalty fees to TPI, it is as if HISI infringes U.S. Patent No. 5,972,401.35

Lastly, both Tan and Ng testified that they wanted to enter into a license agreement with TPI. However, when they heard about the cases filed against TPI, they no longer pursued their intention to secure a license to use the Yamaoka Patent.36

RTC Ruling

On January 25, 2010, the RTC resolved TPI's counterclaims against HISI.37 The RTC found that Frescomar failed to pay the royalties and submit the shipment reports required under the license agreement. However, the RTC declared that Frescomar was no longer liable for the breach since it entered into a Settlement Agreement, where TPI released it from all liabilities.38

Anent the patent infringement issue, the RTC ruled that Frescomar infringed the Yamaoka Patent due to its continued production of the smoke covered by the Yamaoka Patent, even after the termination of the License Agreement. As well, the RTC considered HISI's act of inducing Frescomar to infringe the Yamaoka Patent as contributory infringement. Thus, HISI should be held jointly and severally liable with Frescomar. However, since TPI already waived all its claims against Frescomar, both Frescomar and HISI were no longer liable to pay the damages for patent infringement. Nevertheless, the RTC considered HISI's actions as tortious interference and ordered HISI to pay the following:39

WHEREFORE, the foregoing premises considered[,] judgment is hereby rendered in favor of TPI and against [HISI] ordering the latter to pay the former the following:

1. The amount of [PHP] 5,000,000.00 as damages for tortious interference;

2. The amount of [PHP] 5,000,000.00 as moral damages;

3. The amount of [PHP] 2,000,000.00 as exemplary damages;

4. The amount of [PHP] 2,000,000.00 as and for Attorney's fees; and

5. The amount of [PHP] 1,519,028.73 as cost of suit.

SO ORDERED.40

TPI and HISI filed their respective Motions for Reconsideration, which the RTC denied in a Joint Resolution41 dated March 1, 2011. Both parties elevated the matter to the CA.

TPI insisted that the Settlement Agreement did not absolve Frescomar from its liability for infringing the Yamaoka Patent. Frescomar was still liable for patent infringement, while HISI was liable for contributory infringement.42 On the other hand, HISI maintained that the Yamaoka Patent was not infringed because it covered tuna products, not the smoke. Besides Frescomar's smoke used burning temperatures outside the scope of the Yamaoka Patent. HISI also argued that the dismissal of the unfair competition case carried with it the dismissal of TPI's counterclaims.43

CA Ruling

In a Decision44 dated September 9, 2015, the CA upheld the RTC's grant of PHP 5,000,000.00 as damages but deleted the awards for moral and exemplary damages. The dispositive portion states:

WHEREFORE, the January 25, 2010 Decision of the [RTC] in Civil Case No. 7566 is AFFIRMED with MODIFICATIONS. The awards for moral and exemplary damages are DELETED. [HISI] is ORDERED to pay TPI [PHP] 5,000,000.00 as damages for tortious interference; attorney's fees of [PHP] 1,000,000.00; and costs of suit.

SO ORDERED.45

The CA found the dismissal of the unfair competition case against TPI proper since HISI also moved for its dismissal. However, the dismissal did not affect TPI's counterclaims under Rule 17, Section 2 of the Rules of Court, as amended.46 The CA noted that HISI failed to move for reconsideration of the RTC's order dismissing the unfair competition case and allowing TPI's ex-parte presentation of evidence. HISI only assailed the order after the RTC decided the case in TPI's favor. Accordingly, the CA found no reason to overturn the RTC's order dismissing the case against TPI.47

Also, the CA agreed with the RTC in ruling that Frescomar infringed the Yamaoka Patent even if it only produced the filtered smoke.48 The CA added that the smoke is a by-product of the Yamaoka Patent or a product indirectly obtained from a patented process without the patentee's authorization. Consequently, HISI was liable for contributory infringement.

Likewise, the CA was convinced that Frescomar was willing to pay the royalties were it not for HISI's malicious insistence that the production of the smoke fell under the Kowalski Patent.49 This circumstance led the CA to conclude that HISI was also liable for tortious interference.50

Lastly, the CA upheld the RTC's findings that TPI had already waived any claims due from Frescomar. Under the Settlement Agreement, TPI agreed not to pursue Frescomar and/or Francisco for liability or royalties related to the past infringement of the Yamaoka Patent. As such, TPI had condoned Frescomar's liability. As a result, HISI was also released from liability, being solidarily liable with Frescomar.51 However, HISI remained liable for tortious interference.

Both parties filed their Motions for Partial Reconsideration, which the CA denied in a Resolution dated August 10, 2016.52

Hence, these Petitions.

In G.R. No. 226445, TPI assails the CA's ruling and insists that (1) it did not waive all its claims against Frescomar, (2) HISI cannot benefit from the Settlement Agreement, (3) the attorney's fees should not be reduced, and (4) the moral and exemplary damages should not have been deleted.53

In G.R. No. 226631, HISI reiterates its arguments before the CA that the Yamaoka Patent was not infringed and the RTC should not have dismissed the unfair competition case for failure to prosecute. Also, even assuming the Counterclaim survived, the hearing should not have been made ex-parte. Lastly, the award of damages has no basis.54

Issues

I. Whether Frescomar infringed the Yamaoka Patent and HISI is liable for contributory infringement.

II. Whether TPI released Frescomar from its liabilities for infringement.

III. Whether HISI is liable for tortious interference and TPI is entitled to damages and attorney's fees.

The Court's Ruling

At the outset, Rule 17, Section 255 of the Rules of Court, as amended by A.M. No. 19-10-20-SC, May 1, 2020, provides that a complaint may be dismissed at the plaintiff's instance. If the defendant filed a counterclaim before the plaintiff moved for the dismissal, the dismissal shall be limited to the complaint. In this case, HISI moved for the dismissal of the unfair competition case after TPI filed a Counterclaim. Thus, TPI's Counterclaim may still be resolved in the same action. As well, HISI did not question the RTC's order dismissing the unfair competition case and setting the case for hearing TPI's Counterclaim despite receipt of the order.

With regard to the substantive issues, the Court finds that Frescomar did not infringe the Yamaoka Patent when it produced the filtered smoke even after the termination of the License Agreement. The filtered smoke is not an indirect product of the Yamaoka Patent. Besides, TPI already released Frescomar from its liabilities, following the Settlement Agreement and the Joint Motion to Dismiss. Notwithstanding, HISI is liable for tortious interference by inducing Frescomar to violate the terms of the license agreement.

I.

Frescomar and HISI are not liable for patent infringement

a. Direct and Indirect Patent Infringement

The patent confers on its owner the exclusive right to restrain, prohibit, and prevent any unauthorized person or entity from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing the patented product or product obtained directly or indirectly from a patented process or the unauthorized use of a patented process.56 A violation of this right constitutes patent infringement under Sections 76.1 and 76.6 of the Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines Intell. Prop. Code), which state:

SECTION 76. Civil Action for Infringement. – 76.1. The making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing a patented product or a product obtained directly or indirectly from a patented process, or the use of a patented process without the authorization of the patentee constitutes patent infringement[.]

. . . .

76.6. Anyone who actively induces the infringement of a patent or provides the infringer with a component of a patented product or of a product produced because of a patented process knowing it to be especially adopted for infringing the patented invention and not suitable for substantial non-infringing use shall be liable as a contributory infringer and shall be jointly and severally liable with the infringer. (Emphasis supplied)

There are two kinds of patent infringement—direct and indirect infringement.57 Direct infringement is found under Section 76.1 of the Intell. Prop. Code. It pertains to the making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing the patented product or product obtained directly or indirectly from a patented process, or the unauthorized use of a patented process.

On the other hand, indirect infringement under Section 76.6 can result from a person's act of inducing another to infringe a patent (infringement by inducement), or contributing to the infringement of the patent (contributory infringement).(awÞhi( Contributory infringement requires knowledge on the infringer's part that the component is used for infringing a patented invention and is not suitable for substantial non-infringing use. The same Section makes the person who committed any of the two acts solidarity liable with the direct infringer who is primarily liable for the infringement. Hence, indirect infringement presupposes the existence of a direct infringer. There can be no contributory infringement if there is no direct infringement.

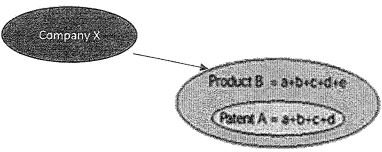

Interestingly, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) illustrated direct patent infringement in this wise:

Let us look at some simple representations in order to illustrate when infringement takes place. We will call the patented invention "A" and the elements contained, in the claims a, b, c and d. The product accused of infringement we will call "B".

Case 1

Patent A includes claims consisting of elements a + b + c + d.

Product B has features covered by elements identical to a + b + c + d; with the addition of element e.

In this case, product B would infringe literally on Patent A, because Product B has all features that are covered by Patent A, even though it has an additional element e.

Case 2

Patent A includes claims consisting of elements of a + b + c + d.

Product B has features covered by identical elements of a + b + c.

Product B may not infringe on Patent A directly, because Product B does not include - literally or equivalently - element d of invention A.

58(Emphasis supplied)

58(Emphasis supplied)

In Case 1, there is direct infringement because Product B contains elements a, b, c, and d of Patent A, despite Product B's inclusion of additional element e. Meanwhile, there is no direct infringement in Case 2 because Product B does not include all the elements of Patent A.

Similarly, in our jurisdiction, if the accused product or process falls within the literal meaning of the claim(s) or the accused product or process appropriates the innovative concept of the patent, and despite the modifications introduced by the accused, it still performs substantially the same functions, in the same way, to produce the same result, there is a direct patent infringement under Section 76.1.59

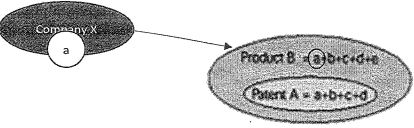

To build on WIPO's illustration and demonstrate indirect infringement under Section 76.6, the Court introduces Company "X" as a third person accused of patent infringement.

Infringement by Inducement

Patent A includes claims consisting of elements a + b + c + d.

Product B has elements identical or equivalent to a + b + c + d; with the addition of element e.

Company X induced the producer of Product B to use the elements in Patent A. In this case, Company X is liable for infringement by inducement, while the producer of Product B is liable for direct infringement.

Contributory Infringement

Patent A includes claims consisting of elements of a + b + c + d.

Product B has elements identical or equivalent to a + b + c + d.

Company X, knowing that element a can only be used in infringing Patent A, provided the producer of Product B with element a. In this case, Company X is liable for contributory infringement, while the producer of Product B is liable for direct infringement. (Emphasis supplied)

Based on the language of Section 76.6 of the Intell. Prop. Code, the infringer by inducement does not appropriate any elements of Patent A. On the contributory infringer, knowing that a component is being used in infringing Patent A and is not suitable for substantial non-infringing use, provided the component of Patent A or a product produced by Patent A. In both cases of indirect infringement, there is a direct infringer, the producer of Product B.

b. Frescomar and HISI are not liable for patent infringement

In the recent case of Phillips Seafood Philippines Corporation v. Tuna Processors, Inc. (Phillips case),60 the Court discussed the two-step analysis and the tests in determining the existence of patent infringement. First, the court interprets the claims to determine the patent's scope and meaning. The claims succinctly state the essence of the invention or the elements which distinguish it from the prior art. Second, it measures the accused product or process against the standard of the properly interpreted claims.

The subject patent in the Phillips case is the same patent invoked by TPI in this case. TPI argues that Frescomar's production of smoke, even after the termination of their license agreement, constitutes patent infringement. Meanwhile, HISI insists that Frescomar's process falls under the Kowalski Patent.

Ordinarily, the court should interpret the claims first, and then determine whether Frescomar's process falls within the scope of the Yamaoka Patent by applying the literal and/or the doctrine of equivalents tests. However, since the RTC and the CA found that Frescomar admitted the use of the Yamaoka Patent, no comparison was made. Consequently, the courts below failed to consider that Frescomar's process of producing the smoke after the termination of the license agreement only appropriates, at most, the first two elements in Claim 1.

It should be stressed that the Yamaoka Patent covers the method of curing tuna meat—not the smoke machine used in producing the smoke. Thus, the core issue is whether Frescomar's continued production of filtered smoke, without performing all the elements in Claim 1, after the termination of the license agreement constitutes patent infringement.

The Court rules in the negative.

Section 75 of the Intell. Prop. Code provides that in determining the extent of protection conferred by a patent, all the elements expressed in the claims and its equivalents shall be considered:

SECTION 75. Extent of Protection and Interpretation of Claims. – 75.1. The extent of protection conferred, by the patent shall be determined by the claims, which are to be interpreted in the light of the description and drawings.

75.2. For the purpose of determining the extent of protection conferred by the patent, due account shall be taken of elements which are equivalent to the elements expressed in the claims, so that a claim shall be considered to cover not only all the elements as expressed therein, but also equivalents. (Emphasis supplied)

Claim 1 of the Yamaoka Patent

The Yamaoka Patent is a process patent covering a method of curing tuna meat using filtered smoke cooled to between 0°C and 5°C, as stated in the following claims:

1. A method for curing raw tuna meat by extra-low temperature smoking comprising the steps of:

burning a smoking material at 250° to 400°C[,] and

passing the produced smoke through a filter to remove mainly tar therefrom;

Cooling the smoke passed through the filter in a cooling unit to between 0° and 5°C[,] while retaining ingredients exerting highly preservative and sterilizing effects; and

smoking the tuna meat at extra-low temperatures by exposure to the smoke cooled to between 0° and 5°C.

2. A method for curing raw tuna by extra-low temperature smoking according to claim 1, in which raw tuna is pre-immersed in a salt water, desalted in cold water, and dewatered before being smoked at said extra-low temperature.61 (Emphasis supplied)

As the Court held in the Phillips case, Claim 1 is the only independent claim in the Yamaoka Patent. The designation of the subject matter of the invention in Claim 1 is a method for curing raw tuna meat by extra-low temperature smoking. The steps are: (1) burning of smoking material at 250° to 400 °C; (2) filtering of the produced smoke to remove mainly tar; (3) cooling of the filtered smoke in a cooling unit to a temperature between 0° and 5°C while retaining ingredients exerting highly preservative and sterilizing effects; and (4) smoking the tuna meat by exposing it to the filtered smoke cooled to between 0° and 5°C.62

The smoke machine used in curing tuna is not protected under Claim 1

The temperatures in burning the smoking material and cooling the filtered smoke are vital in producing the smoked tuna fish. The maximum sterilizing and decomposition and discoloration preventing effects are obtainable when smoking is done using these temperatures.63

Notably, the patent claims do not include a smoking machine. Instead, the smoking machine, which is a conventional smoking apparatus combined with smoke-filtering and cooling units, is disclosed in the patent's DESCRIPTION OF THE PREFERRED EMBODIMENTS,64 which provides:

. . . .

A smoking apparatus of this invention having a construction shown in FIG. 1 is obtainable by adding smoke-filtering and -cooling units to a conventional smoking apparatus[.]65

The patent description discloses the invention "in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art."66 Resort to the description may be done to ascertain the meaning of the terms in the claims,67 but the description can neither limit nor expand the protection of a patent. As stated in Section 75 of the IP Code, the extent of protection conferred by the patent shall only be determined by the claims. Thus, it follows that any unclaimed invention or information disclosed in the description, like the other contents of a patent application and everything that has been made available to the public anywhere in the world, forms part of prior art.68

In the present case, Francisco testified that Frescomar hired the former employees of Pescarich to build a smoke machine patterned from the Yamaoka Patent, with modifications:

Q: So, you hired them purposely to fabricate a smoke generating machine patterned after the machine in a Pescarich Manufacturer Corporation?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Alright. Were they able to construct the said machine?

A: During the construction stage of the machine, when I saw the design I make some modifications immediately in that machine. First, is when I saw that machine that it uses electrical heaters I already know that its going to be expensive to ran the machine with electrical heater so I opted with a cheaper alternative which is using charcoal.

Q: Are you saying that the Pescarich machine which was constructed by Mirasol, Davelos[,] and Makiputin was a design wherein the electric heater was to be the combustive mechanism?

A: Yes, sir. It's supposed to be the heating mechanism to fire.

Q: So, after changing that, did you operate the machine?

A: After changing that I also modified the screw inside where the auger inside the machine.

Q: And what is an auger?

A: The auger is the screw that's pushing the saw dust inside the machine, burning chamber or inside the burning pipe.

Q: So, did you operate the machine?

A: Yes. I did operate the machine.

Q: And what was the result of the operation?

A: We were able to get good quality smoke. When I say good that means smoke with a higher CO concentration and we were able to follow the Pescarich filtration system. And we were able to end up with products, with good products from that machine.69 (Emphasis supplied)

Indisputably, Pescarich's smoke machines are based on the Yamaoka Patent's smoke machines. However, the smoke machine is not protected as an independent claim under the Yamaoka Patent. Accordingly, when Frescomar built its smoke machine, the smoke machine already formed part of prior art. Given that the smoke machine was not mentioned in the claims, the protection of the process under Claim 1 could not extend to the smoke machine.

We are reminded in the Phillips case that the language of the claims limits the scope of protection granted by the patent. The patentees, in enforcing their rights, and the courts, in interpreting the claims, cannot go beyond what is stated in the claims, especially when the language is clear and distinct.

To reiterate, the designation of the subject matter of the Yamaoka Patent's Claim 1 is a method or process of curing tuna meat—not a smoking apparatus or machine. Therefore, the Court's determination of patent infringement, in this case, is limited to the identified elements under Claim 1.

Frescomar did not perform all the elements of Claim 1

Section 76.1 of the IP Code considers the unauthorized use of a patented process as patent infringement. Here, the patented process is the method of curing raw tuna meat by extra-low temperature smoking. The RTC and CA's findings showed that Frescomar used the smoke machines patterned from that of Pescarich's to produce the filtered smoke it sold to HISI. In turn, HISI sold the smoke to seafood processing businesses outside the Philippines.70 Surely, Frescomar did not perform all the elements of Claim I since its process ended with the production of smoke. At most, it performed the first two elements of Claim 1, i.e., burning of smoking material and filtering of the produced smoke, granting Frescomar burned the materials at 250° to 400°C.

As regards the inventive step, there are no findings on whether HISI performed the last two elements of pre-cooling the filtered smoke to between 0° and 5°C before applying it to the tuna meat. It could not be presumed that HISI and/or its buyers of filtered smoke used the extra-low temperature of between 0° and 5°C in curing their tuna products. Clearly, the method for curing raw tuna meat by extra-low temperature smoking protected under the Yamaoka Patent was not completed in this case.

In fine, Frescomar did not use the curing process under the Yamaoka Patent. Thus, the Yamaoka Patent was not infringed.

The filtered smoke is not an indirect product of the Yamaoka Patent

As discussed, Section 76.1 of the Intell. Prop. Code prohibits the making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing the patented product or product obtained directly or indirectly from a patented process.

The Intell. Prop. Code does not define direct and indirect products. However, the WIPO defined the word "directly" in "product obtained directly by that [patented] process" as immediately or without further transformation or modification.71 Thus, considering WIPO's definition of "directly," a product is considered to be directly obtained from a patented process when the infringer deliberately performed the patented process without any attempt to avoid the infringement. Conversely, if there is some attempt to avoid the appearance of infringement by transforming or modifying the process, a product is said to be obtained indirectly from a patented process.

Applying this to the Yamaoka Patent, a product is directly obtained from the patented process if the infringer performed the burning, filtering, and cooling of filtered smoke to a temperature between 0° and 5°C before smoking the tuna meat. On the other hand, if the infringer still smoked the tuna meat using a filtered smoke cooled to a temperature between 0° and 5°C and despite modifications in the process, it still performs substantially the same functions, in the same way, to produce the same tuna products, the resulting product is an indirect product of the Yamaoka Patent.

Here, considering that Frescomar's filtered smoke was produced after burning the smoking material and filtering the smoke, the filtered smoke is not a product directly or indirectly produced from the curing process under the Yamaoka Patent. Rather, it is only a material or component element in producing tuna products under the Yamaoka Patent.

The filtered smoke is not even a by-product because it is not produced in addition to the tuna products. The ordinary meaning of "by-product" is something produced in a usually industrial process in addition to the principal product or a secondary product.72

Given that the filtered smoke is only a material or component element in producing the tuna products, the CA erred in considering the smoke as a by-product or indirect product of the Yamaoka Patent. It should be remembered that Frescomar's filtered smoke is a smoke produced from a smoke machine patterned from Pescarich's smoke machine. Thus, the filtered smoke is not the result of performing the Yamaoka Patent.

Even the definition of "licensed products" under Section 2.3 of the license agreement between TPI and Frescomar supports this conclusion. "Licensed products" is defined as "tuna products produced by processes which, in the absence of this License, would infringe at least one claim of the Yamaoka Patents."73 Apart from not being a tuna product, the smoke produced by Frescomar dees not infringe at least one claim of the Yamaoka Patent because the production of smoke only covers, at most, two of the four elements of Claim 1, i.e., burning of smoking material and filtering of the produced smoke.

All told, Frescomar did not directly infringe the Yamaoka Patent by producing the smoke even if it used the smoke machine patterned after the smoke machine in the Yamaoka Patent. The smoke machine is not an independent claim. Absent any evidence that TPI has a patent protecting the filtered smoke or the smoke machine, the Court cannot hold Frescomar liable for direct patent infringement.

On this score, the Court cannot hold HISI liable for indirect patent infringement. As discussed, the two kinds of indirect patent infringement under Section 76.674 of the IP Code are infringement by inducement and contributory infringement.

Here, HISI induced Frescomar to produce the filtered smoke; however, it was established that the production of filtered smoke does not infringe the Yamaoka Patent. Thus, HISI is not liable for patent infringement by inducement. HISI is likewise not liable for contributory patent infringement. Undeniably, the filtered smoke is an essential component in producing tuna products under the Yamaoka Patent. However, the requirements of knowledge on HISI's part that the smoke is used for infringing the Yamaoka Patent and the smoke can only be used to produce tuna products from the patented process were not proven. It was not established that the buyers of filtered smoke used the extra-low temperature in curing their tuna products or that the smoke has no other use but to infringe the Yamaoka Patent. As the Court noted in the Phillips case, conventional smoking can be done in three temperature zones not covered by the extra-low temperature of 0° to 5°C. Thus, the elements of indirect infringement are absent in this case.

In conclusion, for the past years, the Philippines has preferred the two-part form claim75 under Rule 41676 of the Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations for Patents, Utility Models, and industrial Designs. A two-part form claim contains a statement indicating the designation of the subject matter of the invention and those technical features necessary to define the claimed subject matter but which, in combination, are part of the prior art and a characterizing portion stating the technical features that the claim protects. With this, the performance of some elements of a claim is not sufficient to conclude patent infringement, especially when the accused only used the prior art and did not appropriate the inventive step of the invention. A ruling otherwise would sanction the use of prior art, discourage improvement of a patented product or process, and frustrate the patent laws' purpose of stimulating further innovation.77

II.

TPI released Frescomar from its liabilities for past infringement

Even if the Court considers the smoke as an indirect product of the Yamaoka Patent, Frescomar could not be held liable for patent infringement.

First, TPI agreed not to pursue Frescomar and Francisco for liability or royalties regarding the infringement of U.S. Patent 5,486,619 or its international counterparts. Next, TPI and Frescomar jointly moved for the dismissal of TPI's counterclaims against Frescomar with prejudice, which the RTC granted.78 TPI cannot now conveniently argue that it did not waive any claim for liability due from Frescomar just because the CA found Frescomar liable for infringement.

To avoid confusion, it is necessary to examine the Settlement Agreement79 between TPI and Frescomar. The relevant portion of the settlement agreement, between TPI and Frescomar provides:

a. ...TPI, its officers, directors, employees, agents, servants, and representatives, and Joaquin Lu and his heirs, executors, administrators, successors and assigns release and forever discharge Frescomar and its[] officers, directors, employees, agents, servants, and attorneys, and Francisco [] and his heirs, executors, administrators, successors and assigns, both present and former of or from any and all manner and manners of action, cause and causes of action, suits, debts, demands, controversies, agreements, promises, omissions, damages, judgments, executions, claims, counterclaims, obligations and defenses, whatsoever asserted or unasserted law or in equity, which TPI and/or Joaquin Lu ever had or now have against the Frescomar and/or Francisco [] from the beginning of the world to this date, whether or not presently suspected, contemplated or anticipated, related to the Arbitration action. This release shall not extend to any previously adjudicated liability or any liability for infringement of any patent or patent rights and specifically excludes U.S. Patent 5,486,619 and international counterparts thereof[.]

b. On compliance with the terms of this agreement, TPI hereby covenants not to pursue Respondent Frescomar and/or Francisco [] for liability or royalties related to past infringement of U.S. Patent 5,484,619 or related international counterparts.80 (Emphasis supplied)

TPI's commitment to release Frescomar from its liabilities has two parts. Paragraph a pertains to liabilities relating to the arbitration action that originated from Frescomar's breach of the license agreement, and paragraph b refers to past infringement of U.S. Patent 5,484,619 or related international counterparts, in this case, the Yamaoka Patent.

TPI's contention that "not to [pur]sue" is not the same as "release from liability" is absurd. TPI may not have used the term "release," but it is the necessary consequence of not pursuing Frescomar for its past infringement. "Past infringement" covers TPI's counterclaims in this case since the settlement agreement was executed after the filing of this case. Therefore, TPI's intention to release Frescomar from its liabilities is evident.

Further, the WHEREAS clauses of the Settlement Agreement are more telling of the parties' intentions to settle all their disputes:

. . . .

WHEREAS, Frescomar has breached the license agreement and failed to pay royalties as are due under the license; and

. . . .

WHEREAS, Frescomar commenced two separate actions against TPI in the Philippines in General Santos, Branch 23, General Santos, Civil Case Nos. 7565 and 7566; and

WHEREAS; the parties to this Settlement Agreement wish to compromise and settle all of their disputes[.]81 (Emphasis supplied)

Indubitably, the terms of the Settlement Agreement indicate TPI's intention to release Frescomar from its liability for infringement. This intention was again manifested when TPI joined Frescomar in filing a Joint Motion to Dismiss. The relevant portion of the Joint Motion to Dismiss82 states:

1. The plaintiff FRESCOMAR [] with the exception of Hawaii International Corporation, prays for the dismissal of its action against [TPI] and its officers who likewise, prays for the dismissal of its Counterclaim against the former and its officers, both with prejudice;

2. The plaintiff FRESCOMAR [] and the defendant [TPI] further waive whatever claim or counterclaim they may respectively have against each other arising out of or in connection with the above-entitled case, now and in the future[.]83 (Emphasis in the original, underscoring supplied)

A plain reading of the Motion reveals that TPI voluntarily waived any claim that it may have against Frescomar arising from this case. The Court sees no other reasonable explanation why TPI would agree to move for the dismissal of its counterclaims if it still wants to hold Frescomar liable for patent infringement. More importantly, the RTC already dismissed TPI's Counterclaim against Frescomar with prejudice on October 4, 2007.84 TPI never questioned the RTC's Order. Hence, TPI already waived its claims against Frescomar.

III.

HISI is liable for tortious interference

Article 1314 of the Civil Code provides that "[a]ny third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party."85 The term "induce refers to situations where a person causes another to choose one course of conduct by persuasion or intimidation."86

In So Ping Bun v. Court of Appeals,87 the Court laid down the elements of tortious interference, namely: "(1) existence of a valid contract; (2) knowledge on the part of the third person of the existence of the contract; and (3) interference of the third person is without legal justification or excuse."88

The Court emphasized in Lagon v. Court of Appeals89 that a third person may only be held liable for tortious interference when there is no legal justification or excuse for their action or when their conduct was stirred by a wrongful motive.90 The interference must not be solely driven by the third person's economic or proper business interest. The third person must have acted with malice or must have been driven by purely impious reasons to injure the other party. Malice connotes ill will and implies an intention to do unjustifiable harm to the other party.91

Applying So Ping Bun, the Court finds that all the elements are present in this case.

First, the existence of a license agreement between TPI and Frescomar was established.

Second, the testimonies of Francisco and Eliseo proved HISI's knowledge of the license agreement and showed the reason why HISI insisted that Frescomar should not pay the royalties:

As testified by [] Francisco [] thus:

Q: After the signing of the License Agreement. When you actually signed the License Agreement was Mr. Kowalski or Hawaii International Seafood aware of your actual signing?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And after paying the [USD] 3,000 would you call it initial payment to TPI?

A: Yes, sir. Initial payment to TPI.

Q: Were you able to make subsequent payments?

A: No more.

Q: Could you explain to the Court why you failed to make subsequent payments?

A: During that time when we were not able to pay subsequent payments, I consulted it to [] [ko]walski.

Q: Why?

A: Because he was telling me that I am not suppose[d] to pay royalty payments to TPI because according to him we were not using the Yamaoka Patent and in fact we are already using the tasteless smoke products. So, he made me believe that we were not really using Yamaoka Patent so why should we pay TPI?

Q: You were not using Yamaoka Patent do you mean?

A: Yes, sir. [] Kowalski make me believe that we're not actually using the Yamaoka Patent and in fact that time we were already using the tasteless smoke patent.

Q: Isn't it that the production of smoke as you testified earlier was a smoke generating from the Pescarich patterned smoke machine?

A: Yes, that's why I really believe that we were using a Yamaoka Patent because basically we are using a Pescarich design smoke and that is the same machine that we're using when we're producing tasteless smoke for Hawaii International Seafood.

. . . .

Also, [] Eliseo [], consultant of [HISI], testified, thus:

Q: And when [Francisco] was shipping smoke in containers generated from that smoke generating system using the Pescarich process, were you also aware that [Francisco] had a License Agreement with [TPI]?

A: I am aware, sir.

. . . .

Q: Alright. When [Francisco] showed to you the Demand Letter, what did you do?

A: Immediately, sir, we referred it to [] Kowalski.

. . . .

Q: And what was the reaction of [] Kowalski?

A: Actually it is not only Kowalski, sir, but it was also referred to Mr. Clint Taylor, their order to us is not to pay the royalty to TPI. They ordered [Francisco] not to pay royalty to TPI because according to them paying TPI would only help TPI in their case against Hawaii International Seafood.

. . . .

Q: They have a case. Now, please continue what the exact words or statement made by [] Kowalski?

A: The statement of [] Kowalski and Mr. Clint Taylor is that Frescomar should not pay royalty to TPI because it would help TPI in his case against Hawaii International Seafood. And aside from that, since at the time there's a threat already or I don't know if the arbitration case was already filed by the TPI in the [U.S.]. I don't know there was [a] case filed already in the [U.S.], the arbitration case against Frescomar by TPI. According to Hawaii International Seafood in order for [Francisco] to file a case instead of paying, they advised in order for [Francisco] to file a case here in the Philippines against TPI to preempt the arbitration case in the USA.92 (Emphasis supplied)

HISI, through its officers, acted with malice in ordering Frescomar to stop paying the royalties to TPI. HISI was impelled by its interest to weaken TPI's chances in winning the patent infringement case that TPI filed against HISI in the US upon the expiration of the License Agreement between Yamaoka and Kowalski in 2004. Before TPI filed an infringement case in the U.S., Yamaoka and Kowalski entered into a License Agreement involving U.S. Patent No. 5,484,619, the counterpart of the Yamaoka Patent in the U.S., to prevent the inventors from asserting unlicensed infringement.93

As supported by the RTC and CA's findings, HISI's reason for interfering with the license agreement was its fear that it might benefit TPI in in the US case. HISI's intention to do unjustifiable harm to TPI was also shown when Eliseo ordered Frescomar's employees to tamper with the temperature records to make it appear that Frescomar was using the Kowalski Patent:

Q: And there had been much discussion and production of proof regarding the temperature range or the heating temperature for the production of smoke?

A [Eliseo:]

Yes, sir.

Q: And you were aware that there had been combustion records?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: But were produced to justify that the heating temperature of the so-called Kowalski Patent is higher while the Pescarich process is within the range of 250°C to 400°C, is that correct?

A: I am aware of that, sir, but with the temperature record of Mr. Kowalski was falsified.

Q: What do you mean falsified, Mr. Witness?

A: The temperature records are falsified since there was no actual daily temperature recordings that were read by those who log the temperature record in the forms of the temperature records of Frescomar [] and Hawaii International Seafood Corporation.

Q: Could you be more specific, do you have personal knowledge about that?

A: Yes, sir. Because I was the one who instructed the staff of, in my capacity as Senior Consultant, a representative of Hawaii International Seafood. I was the one who gave instructions to the staff of Frescomar [] to make retroactive records and to make records even though there are temperature readings. And that instruction that I instructed to the Frescomar staff comes from Steven Fisher and Mr. Bill Kowalski.

Q: Why did you instruct them to falsify records?

A: Because there was no temperature records probe and [] Kowalski needs it to be presented in Hawaii Court in his case against [TPI].

Q What about that temperature record, could you explain what is to be falsified, what is to be shown in the temperature records?

A: The instructions of Mr. Kowalski that the numbers that should be put in the records should be more than 650°C up.

Q: Why?

A: Because he wants to show, he wants to prove in the US Courts or in the Hawaii Court that indeed he has a different temperature compared to the Yamaoka Patent.

Q: Is that evidence having any document?

A: Yes, sir. I have emails actually advising them that I have the retroactive records but instead Steven Fisher would reply to me to delete that email and instead phone him.

Q: Did you delete the email?

A: I did not.

Q: Do you have the emails with you?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Kindly show it to the Court?

A: Yes, sir. On March 1, 2005 I sent an email to Mr. Steven Fisher.

Q: And what is the subject of the email?

A: Its smoke generator temperature recording. I would read the email. Dear Steve, since we have now the data for the almost two weeks of our smoke gen operational temperature recording from Frescomar PS Plant should I give the task now to the Frescomar staff to make up retro the records from the January 2004 to February 2005. I am asking this because I know that this is confidential. Regards, Rock. A reply of Mr. Steven Fisher is, delete this and phone me please.94 (Emphasis supplied)

Third, HISI's belief that Frescomar did not use the Yamaoka Patent is not a legal justification. Frescomar's obligations are contractual. Under the license agreement, Frescomar has the obligations to pay royalties for using the Yamaoka Patent in producing its tuna products and request exemption for products produced outside the Yamaoka Patent. If Frescomar believed that some of its products were not produced using the Yamaoka Patent, it must still inform TPI and ask for an exemption. In other words, Frescomar's compliance with its obligations is not dependent on whether the production of smoke falls within the Yamaoka Patent.

More, HISI's interference was not solely based on its belief that Frescomar did not use the Yamaoka Patent; it is also based on wrongful motive. As discussed, HISI did not want Frescomar to pay the royalties because it might weaken its chances of winning in the patent infringement case filed by TPI in the US.

For these reasons, the Court upholds the RTC and CA's findings that HISI is liable for tortious interference.

Damages for tortious interference

Article 2199 of the Civil Code provides that a person is entitled to adequate compensation tor a pecuniary loss that has been duly proved. Such actual or compensatory damages must be proved with a reasonable degree of certainty.95 On the other hand. Article 2224 of the Civil Code allows the courts to grant temperate damages if a party suffered some pecuniary loss but its amount cannot, from the nature of the case, be proved with certainty. Thus, if there is no definitive proof of damages and a person still suffered a loss, temperate or moderate damages can be awarded. The computation of the amount of temperate or moderate damages is usually left to the court's discretion. In all cases, "the amount must be reasonable, bearing in mind that temperate damages should be more than nominal but less than compensatory."96

In tortious interference, the rule is that the defendant "cannot be held liable for more than the amount for which the party who was induced to break the contract can be held liable."97 Ordinarily, the courts consider the amount due to the claimant under the contract. In Go v. Cordero,98 the Court held the defendants liable for the balance of the claimant's contract.99

Surely, TPI suffered some pecuniary loss when Frescomar failed to pay royalties during the effectivity of the license agreement. However, the exact amount of damage or loss is unidentified because no evidence was presented to prove the exact number of tuna products produced by Frescomar during the effectivity of the license agreement. As found by the CA, the record is bereft of any basis to show the actual damages suffered by TPI. However, the Court finds the award of PHP 5,000,000.00 to be unreasonable. Francisco testified that his unpaid royalties in 2005 is around USD 17,000.00 Meanwhile, in a January 13, 2006 final demand letter, TPI sought to claim unpaid royalties of USD 22,534.80 based on Frescomar's shipment records for two years, or during the effectivity of the license agreement. In its Answer with Counterclaim filed with the RTC, TPI's claim rose to PHP 17,233,920.00, without citing the basis of the computation. Considering that TPI's final demand of USD 22,534.80 was based on Frescomar's shipment records, as computed by TPI, and the average Philippine Peso per US Dollar rate in January 2006 is PHP 52.6171,100 the Court finds the award of PHP 1,000,000.00 as temperate damages proper.101

The courts can also grant moral or exemplary damages in tortious interference cases,102 depending on the circumstances of each case. The rule is that a juridical person is generally not entitled to moral damages because it cannot experience physical suffering or such sentiments as wounded feelings, serious anxiety, mental anguish or moral shock.103 Nevertheless, a juridical person can validly complain for libel or any other form of defamation and claim for moral damages,104 but the grant of moral damages to corporations is not automatic. There must be a factual basis for the damage and its relation to the defendant's actions.105

The following requisites must be proven to recover moral damages: (1) an injury, whether physical, mental or psychological, clearly sustained by the claimant; (2) a culpable act or omission factually established; (3) the wrongful act or omission of the defendant is the proximate cause of the injury sustained by the claimant; and (4) the award of damages is predicated on any of the cases stated in Articles 2219106 and 2220.107

In damages, proximate cause is "any cause that produces injury in a natural and continuous sequence, unbroken by any efficient intervening cause, such that the result would not have occurred otherwise.108

Here, TPI presented witnesses to support its claim for moral damages because of lost income and besmirched reputation. Tan and Ng testified that they no longer pursued their intention to secure a license to use the Yamaoka Patent upon hearing about the cases filed against TPI. The Court also notes TSP Marine Industries's letter109 informing TPI that it will no longer use the Yamaoka Patent upon learning about the cases filed against TPI. However, these pieces of evidence show that the proximate cause of the injury sustained by TPI is the filing of the unfair competition case and not HISI's act of interfering with the license agreement and inducing Frescomar to stop paying the royalties. HISI's acts constituting tortious interference could not have been the proximate cause because the damage to TPI's reputation would not have occurred were it not for the filing of the unfair competition case. The filing of the unfair competition case is an efficient intervening cause. Thus, the requisites for the grant of moral damages are absent.

In fine, the CA correctly ruled that TPI is not entitled to moral damages, but TPI is still entitled to exemplary damages. Exemplary damages are awarded to deter future parties from committing a similar offense. In Go v. Cordero,110 the Court awarded PHP 200,000.00 as exemplary damages for tortious interference, after considering the amount of compensatory damages awarded to the claimant.111 Here, HISI acted in bad faith and with malice in interfering with the license agreement and inducing Frescomar to refrain from paying the royalties to TPI. Thus, the Court imposes PHP 500,000.00 as exemplary damages.

Lastly, the Court upholds the grant of PHP 1,000,000.00 attorney's fees, as warranted under Article 2208(1) and (4)112 of the Civil Code. It was established that HISI acted with malice in interfering with the license agreement between Frescomar and TPI and in filing the unfair competition case against TPI. Hence, the grant of attorney's fees is proper.

ACCORDINGLY, the Petitions are DENIED. The Court of Appeals' Decision dated September 9, 2015 and Resolution dated August 10, 2016 in CA-G.R. CV No. 02845-MIN are AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION in that Hawaii International Seafood, Inc. is ORDERED to pay Tuna Processors, Inc. PHP 1,000,000.00 as temperate damages for tortious interference, PHP 500,000.00 as exemplary damages, and PHP 1,000,000.00 as attorney's fees, which shall all earn interest at the rate of 6% per annum from the date of finality of this Decision until full payment.

SO ORDERED.

Gesmundo, C.J., Leonen, SAJ., Caguioa, Hernando, Lazaro-Javier, Zalameda, Gaerlan, Rosario, J. Lopez, Dimaampao, Marquez, Kho, Jr., and Singh, JJ., concur.

Inting,** J., no part.

Footnotes

* Also referred to as Hawaii International Seafood, Inc. in some parts of the rollos.

** No part.

1 World Intellectual Property Organization, IP and Business: Quality Patents: Claiming what Counts, available at https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2006/01/article_0007.html (last accessed on < February 7, 2024>).

2 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), pp. 19-52; rollo (G.R. No. 226631), pp. 8-55.

3 Id. (G.R. No. 226445), at 54-78. The September 9, 2015 Decision in CA-G.R. CV No. 02845-MIN was penned by Associate Justice Henri Jean-Paul B. Inting (now a member of the Court) and concurred in by Associate Justices Edgardo A. Camello and Rafael Antonio M. Santos of the Twenty-Second Division, Court of Appeals, Cagayan de Oro City.

4 Id. at 80-82. The August 10, 2016 Resolution in CA-G.R. No. 02845-MIN was penned by Associate Justice Edgardo A. Camello and concurred in by Associate Justices Rafael Antonio M. Santos and Ronaldo B. Martin of the Special Former Twenty-Second Division, Court of Appeals, Cagayan de Oro City.

5 Id. at 55-56.

6 Id. at 20-21.

7 Id. at 137, 228.

8 Id. at 128.

9 Id.

10 Id. at 128-129.

11 Id. at 62, 64.

12 Id. at 128.

13 Id. at 128-129.

14 Id. at 55-56.

15 Id. at 21-22. See letters to TPI dated September 29, 2005 and January 9, 2006.

16 RTC records (Exhibits-Defendants, Vol. 1). pp 18-19.

17 Id. at 19-21.

18 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 129.

19 Id. at 56-57.

20 Id. at 129.

21 RTC records, pp. 69-90.

22 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), pp. 120-126.

23 Id. at 57.

24 Id.

25 Id. at 127.

26 Id. at 58.

27 Id.

28 Id.

29 See id. at 137, 228. Pescarich succeeded Yamaoka Nippon Corporation.

30 Id. at 62-66.

31 Id. at 58-62.

32 Id. at 62-63.

33 Id. at 64.

34 Id. at 64-65; TSN, October 17, 2008, p. 28.

35 TSN, October 17, 2008, p. 28.

36 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 66.

37 Id. at 128-142. The January 25, 2010 Decision in Civil Case No. 7566 was penned by Judge Andres N. Lorenzo, Jr. of Branch 23, Regional Trial Court, General Santos City.

38 Id. at 129-132.

39 Id. at 137, 141.

40 Id. at 142.

41 Id. at 143-146. The March 1, 2011 Joint Resolution in Civil Case No. 7566 was penned by Judge Andres N. Lorenzo, Jr. of Branch 23, Regional Trial Court, General Santos City.

42 Id. at 68.

43 Id. at 69.

44 Id. at 54-78. The September 9, 2015 Decision in Civil Case No. CA-G.R. CV No. 02845-MIN was penned by Associate Justice Henri Jean-Paul B. Inting (now a member of the Court) and concurred in by Associate Justices Edgardo A. Camello and Rafael Antonio M. Santos of the Twenty-Second Division, Court of Appeals, Cagayan de Oro City.

45 Id. at 78.

46 Id. at 69-71.

47 Id. at 72.

48 Id. at 73-74.

49 Id. at 74.

50 Id. at 76.

51 Id. at 75.

52 Id. at 80-82. The August 10, 2016 Resolution in CA-G.R. CV No. 02845-MIN was penned by Associate Justice Edgardo A. Camello and concurred in by Associate Justices Rafael Antonio M. Santos and Ronaldo B. Martin of the Special Former Twenty-Second Division, Court of Appeals, Cagayan de Oro City.

53 Id. at 43.

54 Rollo (G.R. No. 226631), pp. 48-53.

55 Section 2. Dismissal upon motion of plaintiff. — Except as provided in the preceding section, a complaint shall not be dismissed at the plaintiffs instance save upon approval of the court and upon such terms and conditions as the court deems proper. If a counterclaim has been pleaded by a defendant prior to the service upon him or her of the plaintiffs motion for dismissal, the dismissal shall be limited to the complaint. The dismissal shall be without prejudice to the right of the defendant to prosecute his or her counterclaim in a separate action unless within fifteen (15) calendar days from notice of the motion he or she manifests his or her preference to have his or her counterclaim resolved in the same action. Unless otherwise specified in the order, a dismissal under this paragraph shall be without prejudice. A class suit shall not be dismissed or compromised without the approval of the court.

56 Republic Act No. 8293 (1997), also known as the "Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines."

57 DEBORAH E. BOUCHOUX, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW: THE LAW OF TRADEMARKS, COPYRIGHTS, PATENTS, AND TRADE SECRETS 412 (2016).

58 World Intellectual Property Organization, IP and Business: Quality Patents: Claiming what Counts, available at https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2006/01/article_0007.html (last accessed on < February 27, 2004>.)

59 Godines v. Court of Appeals, 297 Phil. 375, 380-381 (1993) [Per J. Romero, Third Division]. See also Phillips Seafood Philippines Corporation v. Tuna Processors, Inc., G.R. No. 214148, February 6, 2023 [Per J. Lopez, M., Second Division] at 10. This pinpoint citation refers to the copy of the Decision uploaded to the Supreme Court website.

60 G.R. No. 214148, February 6, 2023 [Per J. Lopez., M., Second Division] at 11. This pinpoint citation refers to the copy of the Decision uploaded to the Supreme Court website.

61 Rollo (G.R. No. 226631), p. 275.

62 Id.

63 Phillips Seafood Philippines Corporation v. Tuna Processors Inc., G.R. No. 214148, February 6, 2023 [Per J. Lopez, M., Second Division] at 28. This pinpoint citation refers to the copy of the Decision uploaded to the Supreme Court website.

64 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 106.

65 Id. 106.

66 See INTELL. PROP. CODE, sec. 35.

67 INTELL. PROP. CODE, sec. 75.

Section 75. Extent of Protection and Interpretation of Claims. – 75.1. The extent of protection conferred by the patent shall be determined by the claims, which are to be interpreted in the light of the description and drawings. See also The Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines.

Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations for Patents, Utility Models, and Industrial Designs.

Rule 415. Claims –

. . . .

(d) The claims must conform to the invention as set forth in the description and the terms and phrases used in the claims must find clear support or antecedent basis in the said description so that the meaning of the terms may be ascertainable by reference to the description. Claims shall not, except where absolutely necessary, rely in respect of the technical features of the invention, on reference to the description or drawings. In particular, they shall not rely on references such as, "As described in part xxx of the description" or "As illustrated in figure xxx of the drawings."

68 See INTELL. PROP. CODE, sec. 24. Prior Art.— Prior art shall consist of:

24.1. Everything which has been made available to the public anywhere in the world, before the filing date or the priority date of the application claiming the invention; and

24.2. The whole contents of an application for a patent, utility model, or industrial design registration, published in accordance with this Act, filed or effective in the Philippines, with a filing or priority date that is earlier than the filing or priority date of the application[.] (Emphasis supplied)

69 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 138.

70 Id. at 56, 63.

71 World Intellectual Property Organization, IP and Business: Quality Patents: Claiming what Counts, available at https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2006/01/article_0007.html (last accessed on February 27, 2024).

72 Merriam-Webster Dictionary available at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/by-product.html. (last accessed on February 27, 2024).

73 Rollo, (G.R. No. 226445), p. 60.

74 INTELL. PROP. CODE, Secion 76. Civil Action for Infringement. – . . .

76.6. Anyone who actively induces the infringement of a patent or provides the infringer with a component of a patented product or of a product produced because of a patented process knowing it to be especially adopted for infringing the patented invention and not suitable for substantial non-infringing use shall be liable as a contributory infringer and shall be jointly and severally liable with the infringer. (Emphasis supplied)

75 Bureau of Patents, Manual for Patent Examination Procedure (2017), Rule 416 (a) (b).

76 Rule 416. Form and Contents of the Claims. – The claim shall define the matter for which protection is sought in terms of technical features of the invention. Wherever appropriate, the claims shall contain:

(a) A statement indicating the designation of the subject matter of the invention and those technical features which are necessary for the definition of the claimed subject matter but which, in combination, are part of the prior art;

(b) A characterizing portion preceded by the expression, "characterized in that" or "characterized by," stating the technical features which, in combination with the features stated in subparagraph (a), it is desired to protect[; and]

(c) If the application contains drawings, the technical features mentioned in the claims shall preferably, if the intelligibility of the claim can thereby be increased, be followed by reference signs relating to these features and placed between parentheses. These reference signs shall not be construed as limiting the claim. (Emphasis supplied)

77 See Pearl & Dean (Phil.). Incorporated v. Shoemart, Incorporated, 456 Phil. 474, 490-495 (2003) [Per J. Corona, Third Division].

78 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 127.

79 Id. at 120-126.

80 Id. at 122.

81 Id. at 120.

82 RTC records, pp. 275-277.

83 Id. at 275-276.

84 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), p. 127. The October 4, 2007 Order in Civil Case Nos. 7565 and 7566 was penned by Judge Andres N. Lorenzo, Jr. of Branch 23, Regional Trial Court, General Santos City.

85 Lagon v. Court of Appeals, 493 Phil. 739, 746 (2005) [Per J. Corona, Third Division].

86 Id. at 748.

87 373 Phil. 532 (1999) [Per J. Quisumbing, Second Division].

88 Id. at 540.

89 493 Phil. 739 (2005) [Per J. Corona, Third Division].

90 Id. at 748, citing So Ping Bun v. Court of Appeals, 373 Phil. 532 (1999) [Per J. Quisumbing, Second Division].

91 See Go v. Cordero, 634 Phil. 69, 94-95 (2010) [Per J. Villarama, Jr., First Division].

92 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), pp. 132-137.

93 See Tuna Processors, Inc. v. Haw. Int'l. Seafood. Inc., 327 F. App'x. 204 (2009) [United States of America].

94 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), pp. 139-140.

95 Dee Hua Liong Electrical Equipment Corporation v. Reyes, 230 Phil. 101, 160 (1986) [Per J. Narvasa, First Division].

96 Seven Brothers Shipping Corporation v. DMC - Construction Resources, Inc., 748 Phil. 692, 702 (2014) [Per C.J. Sereno, First Division].

97 Go v. Cordero, 634 Phil. 69, 102 (2010) [Per J. Villarama, Jr., First Division].

98 634 Phil. 69 (2010) [Per J. Villarama, Jr., First Division].

99 Id. at 102.

100 Philippine Peso Per US Dollar Rate, available at https://www.bsp.gov.ph/statistics/external/pesodollar.xlsx (last accessed on February 27, 2024).

101 Rollo (G.R. No. 226445), pp. 75-78.

102 Go v. Cordero, 634 Phil. 69, 103-104 (2010) [Per J. Villarama, Jr., First Division].

103 Filipinas Broadcasting Network, Inc. v. Ago Medical & Educational Center-Bicol Christian College of Medicine, 489 Phil. 380, 399 (2005) [Per J. Carpio, First Division].

104 Id. at 400.

105 Crystal v. Bank of the Philippines Islands, 593 Phil. 344, 355 (2008) [Per J. Tinga, Second Division], citing ABS-CBN Corporation v. Court of Appeals, 361 Phil. 499, 529 (1999) [Per C.J. Davide, Jr., First Division]; Filipinas Broadcasting Network, Inc. v. Ago Medical & Educational Center - Bicol Christian College of Medicine, 489 Phil. 380, 402 (2005) [Per J. Carpio, First Division].

106 Francisco v. Ferrer. Jr., 405 Phil. 741, 749-750 (2001) [Per J. Pardo, First Division]; CIVIL CODE, art. 2219.

Article 2219. Moral damages may be recovered in the following and analogous cases:

(1) A criminal offense resulting in physical injuries;

(2) Quasi-delicts causing physical injuries:

(3) Seduction, abduction, rape, or other lascivious acts;

(4) Adultery or concubinage;

(5) Illegal or arbitrary detention or arrest:

(6) Illegal search;

(7) Libel, slander or any other form of defamation;

(8) Malicious prosecution:

(9) Acts mentioned in Article 309;

(10) Acts and actions referred to in Articles 21, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 34, and 35[.]

107 Arco Pulp and Paper Company, Inc. v. Lim, 737 Phil. 133, 147-148 (2014) [Per J. Leonen, Third Division].

108 Quezon City Government v. Dacara, 499 Phil. 228, 238 (2005) [Per J. Panganiban, Third Division].

109 RTC records (Exhibits – Defendant, vol. 2), p. 480.

110 634 Phil. 69 (2010) [Per J. Villarama, Jr., First Division].

111 Id. at 103-104.

112 CIVIL CODE, art. 2208.

Article 2208. In the absence of stipulation, attorney's fees and expenses of litigation, other than judicial costs, cannot be recovered, except:

(1) When exemplary damages are awarded;

. . . .

(4) In cases of a clearly unfounded civil action or proceeding against the plaintiff[.]

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation